“DON’T GO,” the Tibet-hands hissed at me in the smoky backroom cafés of Lhasa. The word had got around that I was a Lonely Planet writer and Mount Kailash, they argued, reposed in a dimension that couldn’t be encompassed by any ordinary list of things to see and do. At the very least, they chorused, I had a responsibility to do everything I could to discourage my readers from attempting to go there and the best place to start that was by not going myself. It was argument that was not without some insidious logic, but I knew it wouldn’t cut any ice with my editors in Melbourne. Like me, they knew that a rival publisher, Moon, was poised to release the Tibet Handbook, a one-thousand-one-hundred-page doorstopper of a book that provided extensive coverage to all the high plateau’s most sacred pilgrimages.

To the credit of the author, Victor Chan, the book continues to be the most comprehensive guide to Tibet ever published, even if you can no longer visit most of the places it describes.

I had a pre-release version of the book and some thirty pages were devoted to Kailash alone. I was not going to be allowed to meet that challenge with an entry that ran: “It’s too special and holy; don’t go.”

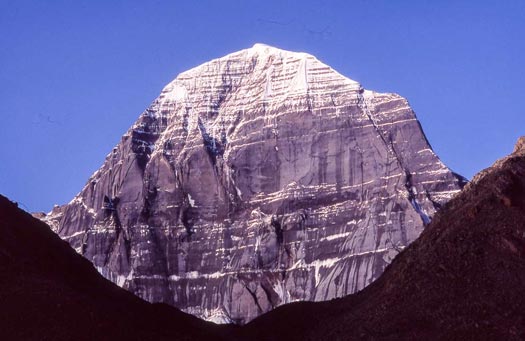

One thousand seven hundred kilometers west of Lhasa, Tibet’s holiest mountain is the approximate source of Asia’s four greatest rivers: the Ganges, the Brahmaputra, the Indus and the Sutlej. It is also the Mount Meru of Hindu legend, mythical abode of gods, eighty-four-thousand towering leagues of gold, crystal, ruby and lapis lazuli. Tibetan Buddhists revere it as the navel of the world. They call it Gang Rinpoche—“Precious Jewel of Snows.”

In other words, I was going. I wanted to go. I had done for close on a decade, since my first trip to Tibet in 1985, when I’d met an Australian who was hitching to Kailash from a tiny windswept hamlet halfway between Lhasa and the Nepalese border. I was traveling from Lhasa to Kathmandu by bus—perhaps the greatest road trip in all of Asia—and the Australian was standing by the roadside with dust in his hair. “Mount Kailash,” he said when I asked him where he was going. “It’s around fifteen hundred kilometers west of here.”

I read Charles Allen’s superb book about Kailash, A Mountain in Tibet, when I got to Kathmandu. From time to time, for years later, I’d remember the Australian. Did he make it? I wondered. What was it like to travail the fifty‑three kilometer kora—pilgrimage circuit—that circumnavigated the navel of the world? I imagined a National Geographic extravaganza: pilgrims prostrating themselves on mountain paths; an ancient Indian saddhu, still, hands raised in prayer high above his head, the snow‑brushed brow of Kailash in the distance, the otherworldly deep blue Tibetan sky overhead.

The problem was getting there. Only one group was planning a Kailash expedition at the time I was in Lhasa, and the advertisement for members, pasted on the Yak Hotel notice board, earnestly exhorted: “Only serious pilgrims need apply.” I wasn’t a serious pilgrim, and even if I could persuade them I was, I didn’t relish the prospect of three weeks in their company. I began to put it about that I was planning a trip to Kailash and that I was looking for one or two people to share the costs of hiring a vehicle to get there. It led me to Alex, an English fashion designer turned student of Buddhism. He’d studied Tibetan in the northern Indian town of Dharamsala—home to the Dalai Lama and Tibet’s government in exile. I was instantly taken by his easygoing, no-bullshit air, and by the sharpness of his mind. Within half an hour we’d agreed to team up and hire a vehicle together.

It was harder than we anticipated. Even then, in 1994, legally traveling to Kailash was expensive. Foreigners had to pay for a permit, hire a four-wheel drive with a driver, as well as a truck to carry supplies. This added up to a bill well beyond the means of a Lonely Planet budget, and it was an avenue we abandoned after hitting dead-ends attempting to haggle at several official travel agencies. Tipped off by locals, our search took us to the back streets of Lhasa—a medieval warren of alleys that encircled the Jokhang, Tibet’s holiest temple. Ultimately, our search took us to the home of Sonam, a diminutive, self-deprecating Tibetan who owned a Chinese-made Dongfeng truck.

I can still see Sonam, hunched over the wheel of his truck in his Chinese-issue blue fatigues, clucking at clouds on the horizon, wiping his rheumy eyes, stoically pushing on with a journey he must surely have regretted soon after it started. I feel sorry for the times I was bad-tempered. He was simply trying to make some money. It wasn’t his fault that he didn’t know the way (The first thing he said to me as we set off from Lhasa at six in the morning was, “Do you have a map?”), or that his truck was eventually going to die, forcing us on a high-altitude desert march that might have killed us. If anyone were to blame, it was Alex and I for attempting a Kailash expedition on a budget that forced us to cut corners.

Cutting corners meant we had sleeping bags but no tent—the back of the truck would do as a place to sleep—and our food supplies were stacked in two cardboard boxes: about one-hundred packets of instant noodles, a dozen or so packets of shortbread biscuits and several dozen bags of miniature chocolate Easter eggs (the only chocolate we could find in Lhasa). We were also taking a gamble on the weather. Just two “roads” weaved their way to western Tibet, and they met approximately at Mount Kailash. We planned to take the northern route in, via the Tibet-Xinjiang trading town of Ali, and the southern route out to the Nepal border. It was a standard expedition plan, but we were running late. If we were held up, the summer rains could make the southern route impassable.

I didn’t worry about any of this particularly, but I can pinpoint when I started to have a nagging sense that the journey wasn’t going to be the most glorious moment in the annals of guidebook writing. It was day three, at a huddle of dismal domiciles called Pongba—a place unlike any other I wrote about for Lonely Planet. It had no waterfall, no beach, no hotel, no restaurant, it just was—one of a handful of grim outposts where human beings somehow got through hardscrabble days (hand-harvesting salt) and nights (drinking) between Lhasa and Mount Kailash. Pongba didn’t have any food or water for sale, only beer. The population of the entire town was to varying degrees alcoholic. The sole street that ran through it was littered with broken bottles and bones—the bottles because the locals sat on their stoops in the evenings, drinking beer and throwing the empties at the packs of dogs yelping into the night; the bones, I assumed, because the bottles sometimes hit their mark. As darkness enveloped us, and Alex and I watched the nightly ritual begin to play out, one of us remarked that it was sad, evidence—if we needed more—of Tibet’s desolation under Chinese rule.

That is, until we’d drained our third beers. Then we joined the party and started throwing the empties at the dogs. I’m not sure who threw the first one. It may have been me. Whoever it was, I recall the moment as a turning point, as if somehow my zeal for writing a guidebook to Tibet sailed away on the arc of that first bottle tumbling through the frigid night air. I absolutely could do nothing to bring tourism to this defeated, desolate place that people passed through as quickly as possible. Pongba was where I stopped taking notes. Pongba was where the journey to Kailash took on an insular logic of its own and acquired imperatives that had nothing to do with writing a guidebook.

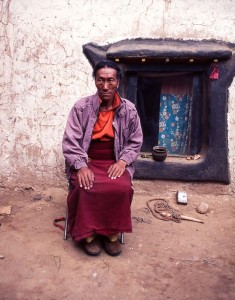

Sonam changed also after Pongba. In the beginning I’d thought he might be a window on Tibet’s most sacred pilgrimage—someone who might help us understand what it meant to be going where we were going from a Tibetan perspective. Perhaps he thought so too. In the beginning, he was guardedly enthusiastic. But by the time we got to Pongba, he began to look as if he’d seen enough. He was along for the ride, he’d do the kora around Kailash with us, but he’d simply taken on an ill-advised job and was making the best of it. He slowly let it leak in a sentence or two, as we bumped along dirt roads and splashed across rivers under a blistering white Tibetan sun, it wasn’t as if anyone at home—at least nobody close to him—would really care that he’d completed the most coveted of all Tibetan pilgrimages: they only cared whether the trip brought in enough money to pay the bills.

In his late forties, Sonam gave the impression—like so many Tibetans I met—of being weary and resigned to whatever life dealt him. He was not a conversationalist, but his story slowly emerged as I spoke with him in Chinese, a language he’d mostly picked up driving trucks in the mountainous southwestern Chinese province of Sichuan. He’d watched Lhasa, the city he’d grown up in, slowly transform into a Chinese city, and was resigned to the fact that the old Tibetan quarter was being dismantled to make way for shabby malls, Chinese restaurants and karaoke parlors. He was also resigned to the fact that his country had been stripped of its nationhood, and that its spiritual leader was in exile and would probably die there. All the old certainties were being steamrollered by a new vision of the future, he said. His children studied in a Chinese-run school and did their lessons in Chinese. If they did their lessons well, they would probably take up jobs in Beijing or Shanghai. Tibet offered little to nothing in the way of opportunities, and children today had little time for the place anyway, he said.

I don’t doubt that our Kailash pilgrimage—particularly the first eight days of keeping our ailing truck alive on the road just to get us there—is seared in Sonam’s memory as it is in mine: The cliffs streaked with white-ribbon waterfalls, the mountain passes, the rolling meadows, glacial moraine valleys, the marmots that stood on their hind legs outside their burrows and made birdlike noises at us everywhere we went: Kailash itself when we finally arrived—an odd, blunt, fist of rock, standing alone, distant from the ranges that mark the initiation of the western Tibetan plateau’s tumbling descent into Pakistan and Nepal.

It was unforgettable, but it was also tough, and Sonam was a man with a job to do; Alex and I were just travelers. None of us was a pilgrim. In Tibet, pilgrims appear on trails that encircle temples, sacred caves, and holy lakes. They throw themselves to the ground, arms outstretched, clamber to their feet, take a step and start again. It’s devotion, self-sacrifice, pain and suffering, self-abnegation—agonies most of us would do anything to avoid. As travelers, the discomfort we’re willing to put up with to prove we’re really travelers is low-grade, abrasive static compared to the punishing trials that Tibetan pilgrims undergo. But when it came to Kailash—at least then—even the pilgrims seemed to waver before that ultimate pilgrimage. I saw none—just knots of vagrants lost on the edge of the world.

***

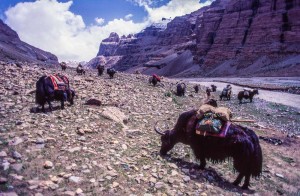

THE ONLY identifiable pilgrims we encountered at Kailash itself was a party of German Buddhists whose entourage included two Tibetan lamas, six porters, eighteen yaks and two chefs. We passed them on a ridge shortly after we’d set off from Darchen, a Pongba-like settlement at the head of the Kailash trail, chatting with them briefly as they paused to take photographs.

That first morning, we took the kora seriously, even tackling a steep detour recommended by the Tibet Handbook to the Cemetery of the Eighty-four Mahasiddhas (a mahasiddha, the Handbook informed us was a “yogic magician”). It wasn’t what the book advertised. It was a sky-burial site, and it unnerved even Sonam. Sky burial tends to get written about in terms that are the preserve of travel writers whose mode is age-old traditions and the mysteries of cultures that have yet to be seduced by McDonald’s. Yes, there’s a poetry to the notion of leaving the dead in high places, offering their remains to the vultures so that they can be carried away into the heavens. But the reality is a gruesome business, the job of a sky burial worker a grim one. The bodies must first be hacked up, and the bones pounded. Surveying the carnage on a small windy plateau, we wrinkled our noses against the stench of decay. The remains of three corpses were scattered around a stone cairn. Two rusty, blood‑stained meat cleavers lay on a nearby rock. No vultures circled overhead. Wild dogs did their work. They began howling and barking almost as soon as we arrived, forcing us back the way we’d come, covering our retreat with hurled rocks.

***

BACK ON THE TRAIL, we found ourselves again amongst the Germans, who were settling down for a lunch of salami, cheese and bread rolls. We wandered a hundred meters or so away, sat down and ate some dry instant noodles. It was a low point. After nine days eating nothing else, we were bored with dry instant noodles. We were also exhausted, and we hadn’t even reached the day’s halfway point. No more detours, we agreed, and we set off for Drira Phuk monastery, where there were said to be beds.

By mid‑afternoon the “pilgrimage” was putting one foot after the other. We were no longer a team. Alex traipsed a couple of hundred meters behind me, Sonam was a distant toiling speck. We failed to cross the Lha River where we should have. That was a mistake, because we were now forced to ford countless fast‑running, ice‑melt streams. At first, I crossed carefully, hopping from stone to stone. But later, I began wading through them. As the sun fell behind Kailash and the shadows lengthened, the air grew chill. My feet—wet and cold—were lumps of pain. The sky clouded over. By the time Drira Phuk Monastery came into view, it was snowing.

The monastery guesthouse was a dilapidated, long, brick building divided into rooms. It sprouted from a rocky outcrop around one-hundred meters below the monastery. Outside a small group of Tibetans in hand‑me‑down People’s Liberation Army uniforms were cooking soup in a massive cauldron. They scowled at me as I approached, and huddled together, muttering in Tibetan. I sat down on a rock and waited for Alex.

I’d long left the Tibetans to Alex. His Tibetan wasn’t good, but he had a pouch of seeds he’d been given in a personal audience with the Dalai Lama. The seeds were saffron red, and whenever we were in trouble Alex would produce them with the show-stopping words, “These seeds were blessed by the Dalai Lama.” The Tibetans swooned. They’d secret their seed away and call out to friends and family members at their good fortune. Dalai Lama seeds are pregnant with merit, bringing fortune to the out‑of‑luck and health to the diseased. More to the point, they’re particularly useful for procuring a place to sleep in the middle of nowhere.

Sure enough, when Alex arrived and presented his pouch of seeds, the Tibetans, immediately wanted to be our friends and share their soup with us. They would even have given us somewhere to stay, if they could. Sadly, they had just moments before finished slapping wet cement onto the floors of monastery guesthouse rooms. Why, I wondered, today? Why not yesterday or tomorrow? Why not next year?

Sonam arrived with a limp and a pained grimace. We sheltered together under the eaves of the guesthouse from a flurry of hail. When the hail stopped, we took a disconsolate tour of the monastery and looked down from on high at the arrival of the Germans—lamas, chefs, porters, and yaks with ribbons in their hair and bells jingling around their necks. It was another somber moment, because we knew we were going to have to throw ourselves at their mercy, and we’d been tipped off already that the head of the German expedition had little time for freeloaders. It was humiliating, letting them know we were in need of help, and then to be told, half an hour later, that our fate was to be decided by a meeting and a vote. Sympathetic elements won by a very narrow margin (so we heard), and we scraped in with the loan of a tent.

The Germans made short work of putting up their tents. Alex and I squabbled over the position of the tent, the function of various poles, where to hammer in the pegs, and finally how to keep the structure earthbound every time a gust of wind threatened to carry it away. The result was a rowdily flapping construction that gave every appearance of being determined to make its escape at the first available opportunity. Sonam watched on, shaking his head and murmuring in Tibetan, and then he wandered off into the darkness with a wave. He had a very comfortable night sleeping on piled up yak‑skin rugs in a nomad tent, he told us the next morning.

We ate with the Germans’ crew of porters. The chefs, two wiry, middle‑aged men from Sichuan, cracked open a fiery bottle of maotai, an evil, gasoline-like concoction made from fermented sorghum, and just as it began to loosen tongues over emptied bowls of chili-laced stir-fries, we were summoned to the Germans’ tent. Alex and I trudged through a bone-chilling wind like prisoners of an ancient war brought before the Great Khan. The German mess tent was deserted but for the group leader and a garrulous man who was the personal pilot of the Sultan of Brunei. We chatted in the flickering light of kerosene lanterns over the remains of the German Buddhist gourmet dinner. I said I was a writer, and Alex said he had retired from the fashion-design business and was now studying Buddhism and working on a novel. In other words, we were impoverished wanderers with literary aspirations. But Alex’s interest in Buddhism was well received—and it gave us something to talk about. Franz, the German group leader and an engineer from Hamburg, his eyes glowing with zeal, described his annual meditation retreats and the long planning and preparation that had gone into this pilgrimage to Kailash.

The pilot broke in, “Life is sterile in Germany. We have everything. We have money, comfort, but there’s no community anymore. Nothing spiritual. Buddhism and meditation puts us back in touch with ourselves. And Mount Kailash is such a holy place. When you stand before this mountain, you forget who you are.”

I had a feeling I was forgetting who I was. It had been more than a week since I’d jotted anything in my notebook or even thought about the guidebook I was supposed to be researching and eventually writing. The ropes whipped in the wind outside. I wondered if our tent was still standing. I had nothing to say to these two men who had come to this barren, hauntingly beautiful place in search of an alternative to a barren Germany. I drifted away, and then I heard the pilot saying, “You know what they say about Kailash? The kora erases the sins of a lifetime. Maybe it’s not true, but it’s better to be safe than sorry, no?”

The wind flung snow in our faces as we stumbled back to our tent. I crawled into my sleeping bag and was immediately smothered by sleep. The next morning, Sonam shook us awake to brilliant sunshine. We dismantled the tent, ate more dry instant noodles and chocolate Easter eggs, and made an early start.

***

THE SECOND DAY of the Kailash kora is the hard one. The challenge is humping it over the five-thousand-six-hundred-and-thirty‑meter Drolma pass and making it down to the other side with both lungs still functioning. Alex and I crossed a fast‑flowing river together close to where we’d camped and slowly climbed a sinuous trail that took us through another sky burial site. Alex stopped to take photographs and I struck off alone. I’d felt vaguely cheated by the absence of Tibetan pilgrims on the first day, so as I descended a hill and saw a family of Tibetans resting on a rock ahead of me, I felt a quickening of excitement. I strode towards them, waved and called out to them cheerily in the Tibetan greeting, “Tashi delay!” They were four—two children, a middle‑aged man and an old woman. They thumbed their prayer beads and eyed me suspiciously. The matriarch, ancient, stooped, her eyes narrow slits of darkness, thrust out a dirty wrinkled hand and croaked, “Dalai Lama.”

Where was Alex and his Dalai Lama seeds when you needed him? I’d run out of Dalai Lama pictures—the gift then that every foreigner was expected to hand out to every Tibetan they met—more than a month ago. I held out my empty hands helplessly, as if to say, “We’re all fellow travellers in this high, beautiful place.” The old woman shrieked in disgust and gestured angrily at me. The two children joined her in an angry chorus. I shook my head and strode away as the family let fly with a further outpouring of abuse. One of the children hurled a rock at me.

I fell into a foul mood. As I walked the anger aggregated: anger at self‑righteous foreign Buddhists; with the Tibetan pilgrims I’d just met; with the Han Chinese who’d torn the heart out of Tibet; and with myself for having momentarily let my skepticism melt away on these high mountain paths where it was easy to feel one really was close to the heavens and enlightenment was just over the next ridge. I tackled the Drolma pass obsessively, competitively, taking occasional peeks behind me to see if Alex was catching up. I scrambled up the narrow path, slipping occasionally on loose gravel and stopping every five minutes or so to catch my breath, gazing down on the valley below, where the Germans were strung out like a long line of ants. When I reached the peak of the pass, I sat beneath a fluttering tangle of prayer flags and smoked my first and last cigarette of the day.

Except for the flap of prayer flags in the wind, it was still and quiet. I was just a thousand meters below the summit of Kailash, and the face of the mountain loomed so close I could almost reach out and touch it, grey and wrinkled with rivulets of ice and strata of rock. My anger melted away. The early start and the rapid ascent meant I had time to kill, and as I sat, wondering how things would have turned out if I’d given that family a picture of the Dalai Lama, and wondering what they were doing in that deserted spot anyway, it suddenly occurred to me that if I pushed on like this I could be back in Darchen by nightfall, completing the pilgrimage in two days instead of three. Darchen beckoned with the promise of hot food, beer and beds.

By the time Alex joined me, I was in high spirits. I told him about my idea of heading back to Darchen a day ahead of schedule. He cautiously agreed, provided we reassess our plans when we arrived at Zutrul Phuk Monastery, where we’d originally planned to overnight, and which was reportedly only around three-hours walk from Darchen.

“By the way,” he said, “did you meet that Tibetan family down there? I gave them some magic Dalai Lama seeds and they let me take their photographs.”

“They threw rocks at me.”

“Maybe they could tell you weren’t a real pilgrim.”

“It’s been something of a problem the entire trip.”

***

WE STRUCK OFF down a slope strewn with massive boulders, hopping from one to the other, pausing occasionally to look for the trail. We found it at the edge of a turquoise lake bristling with massive broken shards of ice. Its Tibetan name translated as the “Lake of Compassion,” according to the Tibet Handbook, and Indian pilgrims, the same tome claimed, came there to immerse themselves in its waters. I’d like to report they were splashing about in droves; we saw none.

Beyond the lake was a steep mountain path that snaked down to the valley on the eastern side of Kailash. It was difficult to keep my footing, and when inevitably I slipped I landed in a nest of nettles that brought my hands and arms up in swollen welts. At the bottom of the pass, I decided to cross to the other side of the Lham River, where the going looked easier. My instincts, it’s now obvious to me, are faulty when it comes to the timing of river crossings. Later, I considered slowing down and waiting for Alex to catch up, but I was reluctant to yield up the pleasure of walking alone, and it was not until after about two hours that I seriously started to look for the others. It worried me that I hadn’t seen Kailash for some time. On the western side of the mountain, it was in view every moment. Here on the eastern side it was an invisible presence. Worse yet, Alex and Sonam also seemed to have disappeared. My stomach screwed itself into a tight knot of anxiety at the horrible thought that I’d missed a turn and was now lost. I sat down and waited. If no one turned up within half an hour, I would start retracing my steps. But before long, Alex and Sonam appeared—on the other side of the river. This was unfortunate because the river that had been so easy to ford three hours upstream was now wide and swollen by melt‑ice tributaries.

I walked down to the water’s edge and attempted to get a measure of its fury by the dubious means of tossing in a few stones. Alex and Sonam watched from the far side of the turbulent deluge. I decided the best approach would be to edge in slowly. If the water was too deep, I could always edge back the way I’d come and find a safer crossing. I edged in. It was water from high mountain places, shockingly cold, liquid ice. It tugged and pulled and splashed about my knees, and then at my waist. I hoisted my camera bag onto my shoulder. In the middle, I thought for a terrible moment that it was too dangerous to go on. I pushed ahead, tripped on a rock and floundered briefly. Then the water was again tugging at my knees and I was wading out, shivering and dripping.

I trudged out from the river. Alex was doing his best not to laugh.

“You were on the wrong side of the river,” said Sonam.

***

WE REACHED Zutrul Phuk monastery at around four in the afternoon. The guesthouse had rooms, but no beds, and no food, which clinched the decision to carry on and walk the last three hours to Darchen. We walked in silence, following the lip of a gorge out to the edge of the sprawling Bakhar Plain, an empty expanse of grit and lumpy earth where the wind gusts and sometimes, on days like this one, the rain falls as hard as hail. It whipped and stung like flung gravel, and the wind sliced through my sweater. I’d brought a down jacket, but I’d given it to Sonam, who had nothing warm to wear. I searched the distance behind me but I couldn’t see him. I hugged my arms to my chest and staggered on.

Lack of food, exhaustion and the cold began to defeat me. I felt frail and waiflike. I couldn’t stop thinking about my home and my wife and my baby son. Tears coursed down my cheeks. This is stupid, I thought. It was my idea to complete the kora today. I’m not going to let everyone down by collapsing with exhaustion. But I felt dangerously weak and tired. I had a feeling I might even die, and the thought of death brought back the tears. This is stupid, I thought again. I’m not going to die. Not here. Not now. Not on a two‑day walk around a mountain.

I once saw a documentary about an Antarctic expedition. A man was sitting in a tent and outside was a swirling whiteness of snow and wind. He was talking to the camera about how he was lonely and missed home and was tired of the cold, the wind and the snow, and he began to weep inconsolably. I could picture him huddled in fetal misery in his tent. I knew how he felt. I thought of all the people who must have died alone in faraway places and I felt horribly sad. And just a few hundred meters from Darchen, I sat down on a rock, and thought about lying down and taking a nap and resting. Alex was somewhere ahead of me. He stopped, turned around slowly and gazed at me. He beckoned with his arm. I nodded wearily. This is stupid, I thought. I climbed to my feet and slowly, shivering, made my way into town.

Alex and Sonam put me to bed inside two sleeping bags and piled all the blankets and quilts they could find over me. It was hours before I stopped shivering. My last memory of that night was Sonam standing by my bedside and pronouncing, “He’ll be very sick. We’ll have to wait here in Darchen for him to get better. It might take a long time.”

But the next morning I was up early and sitting outside in the sun, drinking instant coffee and smoking a cigarette with Alex. A French couple turned up from nowhere. They’d walked for two weeks from the town of Ali to reach Kailash. I felt humbled. We made them coffee and collected our store of shortbread biscuits from the truck. I don’t remember what we talked about, just that they seemed like wonderful people. Everybody seemed wonderful: Alex, Sonam, the staff at the guesthouse, the German pilgrims even.

A Tibetan porter came to us with a friend and asked if they could go to Lhasa in the back of our truck to look for work. We agreed. We helped Sonam load the truck, and at midday we drove for a couple of hours to Lake Manasarovar, where we spent an afternoon and a night in a small guesthouse beside a monastery perched on a crag overlooking Tibet’s holiest lake. The next day we delivered a photograph of a monk Alex had met in Dharamsala to the monk’s family. They lived in a small village on the eastern flank of the lake and they directed us to the home of a reincarnate lama. He sprinkled us with holy water and said prayers over us.

***

THE PRAYERS and the holy water were of no help—or at least not in the short term. The next day, as night fell, the truck broke down. We spent the night in the cargo bed, and the next morning Sonam began taking everything apart, laying out all the bits on a piece of tarpaulin. He finally came up with the culprit, shaking his head ominously—a sprocket‑like device from the transmission whose teeth had worn away.

“Can you fix it?”

“No. We have to get a new one.”

“Where are we going to get that?”

Sonam shook his head uncertainly and shrugged: “Lhasa. Maybe Shigatse.”

We took it in turns to stand on the roof of the truck and look for approaching vehicles. In the searing heat of the midday sun we sheltered beneath the truck. There was nothing much we could do except wait for someone to pass by and hope they would give us a lift to somewhere.

It was late in the day we saw it—a faint plume of dust on the horizon. We watched its progress excitedly. “It’s a truck,” I guessed. “It’s two trucks,” Alex said. The dust settled and some dots—presumably tents—appeared on the plain several kilometers away. It was a tour group, we decided.

“If it’s a Western tour group,” I said to Sonam, “we’re probably in luck. They won’t leave us stranded out here. I expect they’ll give us a lift to the next town.”

Sonam raised his eyebrows. He’d come to his own conclusions about the well-equipped foreign pilgrimage expeditions bound for Kailash.

Alex and I took a short cut along the edge of a brackish lake and across some sand dunes dotted with tufts of grass. An hour-and-a-half later we came into view of the camp. We were gaunt and filthy, two weeks without a shower, washing our faces and hands in streams with no soap, and sustained only by dried instant noodles and miniature chocolate Easter eggs, the occasional shortbread biscuit. Confronted with a camp that was a model of efficiency, we were aware of how we must have looked. A neat row of tents nestled beside a four-wheel drive and two trucks. A tall, blond, stereotypically athletic Californian straightened up from what he was doing and watched our arrival. An American voice cried out: “Popcorn’s ready!” The man nodded in our direction, and several people coalesced around him.

“Hi. We’re camped over there,” I said gesturing in the distance behind me.

“We saw you.”

“We saw you too.” I felt like I’d got off to a bad start.

Alex took over, and as he chatted with the Americans I wandered off to talk to the Chinese drivers. There was a town called Paryang a couple of hours drive down the road, they said. They weren’t leaving the next morning until around nine, and, yes, one of them was prepared to leave at dawn, take us as far as Paryang, and be back in time to pick up the Americans if Alex and I threw him some money and the Americans went along with the idea.

When I rejoined the Americans, one of them was saying: “Gee, guys, I can’t see how we can help.”

I told them about my conversation with the drivers, but before I’d finished a bald, thickset man at the back burst out: “No way, no way.”

He initiated a chorus of support.

“We’d like to help …”

“We’re on a very tight itinerary …”

“If anything went wrong …”

“There’s a bad river crossing up ahead …”

“If the truck got stuck there, well, the expedition would be screwed.”

“It’s not that we don’t want to help …”

I cut through the clamor: “We’re going to have walk it, in other words.”

“You should be okay,” the group leader said. He sounded uncertain. “It’s probably around five hours.”

As Alex and I sloped off into the darkness, a distant cry floated out: “Hey, guys! We’ll say some mantras for you!”

Alex said quietly, “I’m very disappointed with the pilgrims I’ve met on this trip.”

The next morning the porters joined us reluctantly to help out with the luggage. They had to be back by nightfall to look after the truck. Sonam came too on a quest for his sprocket. By mid‑morning we were out of drinking water and we still hadn’t reached the river. The porters dawdled and complained until we took the luggage ourselves. They parted with embarrassed smiles and strolled off back in the direction of the truck. It was midday before we reached the river, which was muddy and fast flowing. We debated whether we should drink from it, and didn’t. We crossed it naked but for our underwear, our clothes, shoes and bags held over our heads.

An hour from the river we arrived at a cluster of Tibetan homesteads that skulked low on the ground like small walled fortresses, indifferent to the world: shuttered windows and heavy wooden padlocked doors. A pack of slavering dogs shadowed us, howling and barking. A man came out and took us into his home. We gave him and his wife Dalai Lama seeds and their child chocolate Easter eggs. They gave us hot water. We drank gallons of it and rested in the cool darkness of their home.

We set off again in the hot mid‑afternoon sun. The trail wove between sand dunes that shimmered in the heat. Within an hour we’d run out of water again. My pack, stuffed with three cameras and lenses, a tripod, a dozen books, a sleeping bag, clothes and notebooks, was like a dead body on my back. In a rutted dried‑out marsh—Paryang a distant, dusty splotch on the horizon—I threw it to the ground and kicked it and cursed its existence. Then I picked it up, hoisted it onto my back, and started walking.

Two hours later, I stumbled into Paryang. It was a place of dust and flies, of windowless walls, of broken glass and bones, and locals who stared dully with squinted eyes from the shadows. I found Alex slumped in the shade of a wall. I slithered slowly to the ground at his side. We’d been walking for close on twelve hours.

“Have you seen Sonam?” I asked.

He shook his head.

“Have you seen a shop?”

Alex went away. He came back ten minutes later with two big bottles of warm orangeade. I took one and gulped it down. A man appeared and led us to a room. Inside were four mattresses laid out on platforms of pounded dirt. The man’s daughter brought us water, beer and food. We ate and drank, sitting on the beds. Sonam staggered in, collapsed on an empty bed, and slowly, quietly and with great emphasis moaned the only word of English I ever heard pass his lips: “Fuck.”

***

THE NEXT MORNING, we hired a truck for another town, where we parted ways with Sonam. He had a sprocket to buy. Sonam felt bad his truck had let us down; we felt bad we weren’t seeing the journey through to its end with him. Worse, I had a feeling we’d left him sadder and wearier than before we met him.

Later that day Alex and I hired another truck for the next morning and continued on to the Nepal border. We traveled mostly in silence, but when we reached our last overnight stop before the border that evening, a town called Saga, we bought a bottle of cheap Chinese brandy and drank it from tin cups in a dank room by candlelight. We talked for hours. It wasn’t the Tibet that Alex had fallen in love with in Dharamsala, where the Dalai Lama and his court waited in exile. But he couldn’t decide precisely what Tibet it was we’d traveled through. It was almost a place that belonged to nobody. The Chinese claimed it as theirs. It wasn’t. But it also wasn’t the Tibet Westerners like us claimed as ours—its sacred, remote places. Tired and confused, we circled uncertainly, searching for something that would make sense of it, all the while in love with this broken Himalayan culture in a desperate against-all-hope kind of way. We mistrusted ourselves for the same reasons we mistrusted the Western pilgrims. If we were in love with anything, it was a love of empty places and lost things—an isolating gaze, the camera lens that squeezes past the billboards and the smokestacks and picks out a distant minaret in search of the postcard view. It was desperately sentimental, a hopeless longing for something gone or something that might have been. In Lhasa—and this was long before Tibet became a police state, often locked down and off limits for foreign tourists—we’d seen evidence then of positive change. Temples and monasteries destroyed by the Chinese, or by the Tibetans themselves at gunpoint, were being restored and rebuilt, and that in turn was restoring Tibetan dignity even as the Tibetans themselves became a minority in their homeland. But on the long road to Kailash and back, we’d been witness to another story: well-provisioned, fully self-sustaining teams of tourists who cocooned themselves against the realities of Tibet so that it could play out as a cinematic backdrop to their fantasies about Buddhist pilgrimage. We saw no Tibetans pilgrims. I don’t think we understood this at the time, but pilgrimage had already become an equivalence of privilege—and since that journey so long ago, I can only imagine it has become more so.

***

THE NEXT DAY we drove to Zhangmu on the Nepal border. It was green and lush, a riot of vegetation and chattering mountain streams. Alex and I ate curries in a Nepalese restaurant with a hysterical Tibetan monk who wept one minute and shrieked the next about the Chinese invasion of his country.

After dinner, we played pool over a couple of bottles of beer in a wooden shack. A Tibetan woman watched us play.

“Your Chinese is very good,” she said, after hearing me order drinks.

“Thank you.”

“Have you been travelling in Tibet?”

“Yes. We went to Mount Kailash.”

“The Sacred Mountain?”

“Have you been?”

“No. It must be a primitive place. Did you go to Lhasa too?”

“Yes.”

“That must be fun. There are karaoke parlors there, aren’t there?”

“Yes.”

“If I was you I would’ve stayed in Lhasa. I don’t think it could have been much fun at Mount Kailash.”

I might have told her about erasing the sins of a lifetime and being better safe than sorry, but I didn’t. She had a pretty face and a twinkle in her eye. What did she want with sins and suffering and pilgrimage? I bought her a beer and she beat me at pool, giggling innocently as she potted the black.

Harvest Season, a novel, is now available in print and digital formats.